Estimated Time to Read: 9 minutes

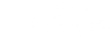

Texas voters have approved more than 500 constitutional amendments since the current state constitution was adopted in 1876. That number, 706 proposed amendments in total, is unusually high by any measure. While many states treat constitutional changes as exceptional, Texas treats them as routine. Understanding why requires looking at how the state’s constitution was written, how the legislative process works, and how Texas voters typically engage with these proposals.

A Constitution Written for Gridlock

The Texas Constitution was born out of post-Reconstruction distrust in government power. Its framers deliberately drafted a restrictive, detailed document that limited the authority of the state and required voter approval for even relatively minor actions. Unlike the U.S. Constitution, which outlines broad principles and allows legislatures to work out the details, the Texas Constitution locks in specifics about taxation, debt, governance structures, and local authority.

Because of this rigidity, the Legislature cannot pass certain policies, particularly those related to local authority, fiscal matters, or government structure, without first amending the Constitution. That is why Texans see amendments on their ballots nearly every election cycle. They are often not about sweeping social change or major rights issues, but more often than not about allowing counties to issue bonds, authorizing tax exemptions, or altering administrative procedures.

A State That Amends More Than Most

Since 1876, Texas lawmakers have proposed 706 constitutional amendments. Of those, 521 have been approved and 185 have been rejected, meaning roughly three out of four proposed amendments have been adopted. That success rate is remarkable, especially considering how frequent the proposals have become.

Source: Data provided by Legislative Reference Library of Texas

When compared to other states, Texas is an outlier. California, often known for its extensive ballot initiatives, has had just over 500 amendments since adopting its constitution in 1879. Florida, which ratified a new constitution in 1968, has seen fewer than 150 amendments. New York, which, like Texas, has a large population and a similarly old governing document, has passed fewer than 250. Even Georgia, whose current constitution dates to 1983, has amended it fewer than 100 times.

What makes Texas’s case even more notable is that its amendment process is entirely legislative. Unlike California or Florida, citizens cannot initiate constitutional amendments via petition. Every single one must begin in the Texas Legislature, pass with a two-thirds vote in both chambers, and then be submitted to voters. The result is a state constitution that functions more like a super-sized law book than a foundational charter of governing principles.

Why Most Amendments Pass

Texas voters have a long history of approving constitutional amendments. There are a number of reasons for this trend, starting with simple familiarity. Texans are accustomed to seeing constitutional amendments on the ballot every two years. Over time, this regularity has created a sense that such measures are ordinary, just another part of the democratic process. Voters are more likely to approve something that seems routine, especially when it lacks controversy or media attention.

In many cases, the language used to describe amendments is part of the issue. While the Texas Legislative Council is responsible for writing ballot language that is meant to be clear and nonpartisan, the summaries are often vague or framed in ways that emphasize the benefits while downplaying tradeoffs. Phrasing like “authorizing a political subdivision to issue bonds for infrastructure improvements” sounds helpful, but it rarely communicates the full scope or financial implications. Without context, voters tend to give the benefit of the doubt and vote yes.

Another major factor is the absence of organized opposition. Most amendments are not controversial enough to generate public resistance. They pass quietly, particularly in lower-turnout elections, where the electorate is often smaller and more civically engaged. These voters may be more likely to trust the Legislature’s judgment or may simply default to approval when a proposal lacks red flags.

Bipartisanship adds another layer of perceived legitimacy. When lawmakers from both parties unite behind a proposed amendment, voters often assume the measure is sensible. Even those who are generally skeptical of government are less likely to object to something that has received near-unanimous support in the Legislature.

There is also a cultural component to consider. Texans generally value local control, limited government, and constitutional government. Amendments framed around those values, even if the reality is more complex, tend to pass more easily. That trust in “the Texas way” creates an environment in which most constitutional changes are viewed favorably.

When Amendments Fail

Although most amendments pass, roughly 25 percent are rejected. Those that fail typically share some common traits. Proposals that involve new or expanded taxes, large-scale bonding authority, or major structural changes tend to face greater scrutiny. If voters believe an amendment benefits special interests, expands government, or carries hidden costs, it is more likely to be defeated.

Amendments that fail also tend to suffer from poor communication. If the language is confusing or the implications are unclear, voters often default to “no.” This is particularly true when the measure lacks a compelling explanation or when watchdog groups raise red flags about unintended consequences. A single well-organized campaign, especially from liberty-minded or taxpayer advocacy groups, can sink an otherwise low-profile proposal.

What This Tells Us About Texas Governance

The sheer volume of amendments reveals a deeper truth about the structure of Texas government. The Constitution is overloaded with policy details that other states would manage through ordinary legislation. Lawmakers in Texas have learned to treat the amendment process not as a rare opportunity for constitutional refinement, but as a tool for routine policymaking.

This reliance on constitutional amendments allows the Legislature to bypass statutory limits or constitutional constraints without passing comprehensive reforms. Need to authorize a local government to issue bonds or adjust tax rules for a niche industry? Just propose an amendment. The document continues to grow, not necessarily because of ideological shifts, but because its structure demands it.

Why a Streamlined Constitution Supports Limited Government

Supporters of limited government should be the loudest voices calling for constitutional clarity and restraint. A constitution is meant to define the framework of government, not manage every policy detail. When the constitution becomes a catch-all for bond approvals, tax exceptions, and regulatory carve-outs, it dilutes its authority and blurs the line between principle and politics.

A streamlined constitution rooted in individual liberty and constitutional boundaries would offer several benefits. First, it would restore the proper balance between governing institutions. By defining what government may and may not do, without micromanaging how it does it, a reformed constitution would place real constraints on government power while leaving flexibility for future legislatures to respond to the needs of Texans without constantly rewriting the state’s foundation.

Second, a leaner constitution would increase transparency. Voters would no longer be asked to approve legalistic, obscure amendments that require hours of research to understand. Instead, they would know that constitutional amendments were being reserved for truly foundational changes, such as limiting taxes, protecting rights, or restructuring governance.

Third, it would reduce the influence of special interests that currently use the amendment process to secure favorable treatment. Whether it is carving out exemptions for certain industries, creating complex financing schemes, or embedding pet projects in the Constitution, the current process often favors well-connected insiders. A cleaner constitution with firm limitations makes it harder to rig the rules of the game.

Finally, streamlining the constitution would encourage a healthier legislative process. It would restore the distinction between constitutional governance and ordinary lawmaking. That separation is vital for preserving self-government, preventing overreach, and ensuring that elected lawmakers, not the Constitution itself, are accountable for the laws they pass.

Texans should not have to vote every two years on whether a rural district can issue road bonds, whether a specific property tax exemption should apply to a niche group, or whether a university fund should be slightly restructured. These are legislative decisions. And by stuffing them into the Constitution, we erode its meaning and burden voters with questions that should never rise to the level of constitutional reform.

For limited government advocates, the path forward is clear: fight for a constitution that limits power, protects liberty, and resists the temptation to do too much.

How Voters Can Make Informed Decisions

If Texans are expected to vote on constitutional amendments every two years, they deserve the tools to evaluate what these proposals actually do. The best place to start is with the 2025 Constitutional Amendment Ballot Guide and Vote Recommendations published by Texas Policy Research. This resource breaks down each proposed amendment in plain language and provides vote recommendations based on principles of individual liberty, limited government, and fiscal responsibility. You can find the full guide here.

Voters should also take the time to read the official Texas Voter Guide, published by the Texas Legislative Council, which provides nonpartisan summaries of each measure. Reading summaries is only part of the equation, however. Voters must ask whether a proposed amendment actually belongs in the Constitution at all. Would the issue be better handled through regular lawmaking? Is the measure permanent in ways that could be hard to undo? And does it expand the role of government or protect liberty?

Amendments are not just policy decisions; they are permanent changes to the state’s foundational governing document. They deserve the same level of scrutiny as legislation, if not more.

Conclusion

Texas has one of the most frequently amended constitutions in the nation. That is not a reflection of how participatory or democratic the state is. It is a consequence of a poorly designed constitution that micromanages public policy and forces voters to decide questions better left to statutes. The amendment process has become so routine that it risks losing its constitutional significance.

As Texas continues to grow and its government becomes more complex, the need for structural reform will only increase. Until then, voters should view every constitutional amendment with skepticism, look beyond the ballot summary, and ask whether the measure strengthens liberty or simply grows government.

Texas Policy Research relies on the support of generous donors across Texas.

If you found this information helpful, please consider supporting our efforts! Thank you!