Estimated Time to Read: 20 minutes

Texas school finance determines how public schools receive money, how much taxpayers contribute, and how the state equalizes funding across communities with very different levels of property wealth. The system is complex, but the stakes are enormous. Public education spending now accounts for more than one-third of the entire Texas state budget, making school finance not only an education issue but one of the most significant fiscal challenges in state government. Every decision about formulas, appropriations, and property taxes carries budget-wide consequences for both taxpayers and state lawmakers.

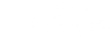

Texas funds its public schools through a mixture of local property taxes, state general revenue, dedicated education funds, and a redistribution mechanism known as recapture. All of this revenue flows into the Foundation School Program, where statewide formulas determine how much money school districts and charter schools ultimately receive. Although the system can appear technical, understanding the structure is essential for evaluating property tax burdens, district spending, and the state’s long-term financial obligations.

A Brief History of Texas School Finance

Texas did not always rely on the complex structure used today. The system grew through several major turning points.

Early Uniform Funding

Texas’s earliest school finance system, dating back to the late 1800s, relied primarily on statewide funding mechanisms rather than local taxation. The state distributed money on a per-capita basis, sending a uniform allotment for every eligible student. This ensured that children in small rural districts received the same level of state support as those in major cities.

This early structure prioritized equal treatment of students across the state and intentionally minimized local disparities. At this stage, school funding was not based on local wealth, and the state played the dominant role in ensuring a baseline level of educational opportunity. Local communities had little fiscal authority, and the state’s allocation was intended to operate as a uniform guarantee.

As Texas’s population expanded and communities sought more customized or advanced educational services, the limitations of this uniform funding model became more apparent, setting the stage for the next major shift.

The Rise of Local Property Taxes

In the early and mid-twentieth century, Texas granted school districts the authority to levy local property taxes as a means of supplementing state funding. This shift marked a fundamental turning point. It allowed communities with higher property values to raise significantly more revenue than property-poor districts, even at identical tax rates.

Local property taxes quickly became the dominant revenue source for public schools. By the mid-1900s, most Texas school districts relied heavily on local taxes for staffing, facilities, and enrichment programs. This change introduced a structural disparity into the school finance system because property values differ dramatically across the state.

Districts with major industrial, commercial, or mineral bases could generate robust funding with modest tax rates. Districts with low property values struggled to raise adequate revenue even with high tax rates. That divergence eventually set off decades of litigation over whether reliance on local property taxes created unconstitutional inequities.

The Gilmer Aikin Reforms

The Gilmer Aikin reforms are named for State Rep. Claud Gilmer (D-Rocksprings) and State Sen. A. M. Aikin Jr. (D-Paris), the two lawmakers who led the effort to modernize Texas public education in the years following World War II. Gilmer served as Speaker of the House and chaired the statewide commission charged with studying Texas public schools. Aikin chaired the Senate Education Committee and carried the reform legislation in the upper chamber. Their partnership produced one of the most significant overhauls in Texas education history, and the reforms now bear their names.

The reforms were enacted during the 51st Texas Legislature in 1949, culminating in a package of legislation built around Senate Bill 116, which created the Minimum Foundation Program, the first statewide guarantee that every district would receive a basic level of funding necessary to provide an adequate public education. The bill also modernized school administration, strengthened statewide oversight, and laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the Texas Education Agency.

Other companion measures passed during the same session reorganized teacher certification, professional standards, and state-level governance. Together, these laws reshaped the structure of public education by establishing the principle that the state bears responsibility for ensuring a minimum funding standard while local districts retain the authority to levy property taxes for additional support.

Although the Gilmer Aikin reforms did not address the disparities created by uneven local property wealth, they created the foundational framework that later generations of lawmakers, courts, and policymakers would reinterpret and expand. The Minimum Foundation Program created by SB 116 is the conceptual predecessor to today’s Foundation School Program and remains a defining milestone in the evolution of Texas school finance.

Litigation and the Creation of Recapture

The creation of recapture stems directly from a series of landmark legal cases known collectively as the Edgewood decisions. The major cases are:

- Edgewood I (1989): The Texas Supreme Court ruled that the school finance system was unconstitutional because wide disparities in property wealth created an inefficient and inequitable system. It held that the Legislature must provide “substantially equal access to similar revenues.”

- Edgewood II & IIa (1991): The Court rejected the Legislature’s first attempt at reform (county education districts), finding that it created an unconstitutional statewide property tax.

- Edgewood III (1992): The Court struck down additional funding arrangements, pushing lawmakers toward a structural solution rather than temporary fixes.

- Edgewood IV (1995): The Court finally upheld a plan that included recapture, where wealthier districts with property values above certain levels would return excess revenue to the state for redistribution.

These rulings transformed school finance in Texas. The Court forced the state to equalize funding and declared local tax effort insufficient on its own to ensure constitutional adequacy. Recapture was the Legislature’s solution. It remains in place today and continues to grow as property values increase.

Tax Compression and the Modern Structure

Later court rulings determined that district tax rates had become a de facto statewide property tax. To comply with constitutional limits, lawmakers compressed local tax rates and increased the state’s share of funding. This placed more responsibility on the Legislature and made the system increasingly dependent on statewide revenue.

- West Orange–Cove II (2005): The Texas Supreme Court held that school district maintenance and operations tax rates had become a “de facto statewide property tax,” which is prohibited by the Texas Constitution. Because almost every district had raised taxes to the statutory maximum, they no longer had the meaningful discretion required for the tax to be considered local.

The Legislature responded in 2006 by significantly compressing local school tax rates and increasing the state’s contribution to the Foundation School Program. This created the modern cycle of legislative tax compression.

Compression has remained a major tool for tax relief. Texas Policy Research views compression as the superior method of reducing property taxes because it lowers rates for all taxpayers instead of relying on targeted exemptions that shift the burden onto those who do not qualify.

The Growth of Student-Centered Reforms

More recently, Texas expanded educational options with the creation of charter schools and, now, Education Savings Accounts (ESAs). These programs represent a shift toward funding students directly rather than funding districts exclusively. ESAs in particular reflect a move toward empowering families rather than defaulting all resources through district formulas.

Today, the system is an amalgamation of statewide formulas, local taxes, redistribution mechanisms, and emerging student-centered reforms. Understanding this history clarifies why the system looks the way it does today and why structural reform is both possible and needed.

Understanding the “Tiers” in Texas School Finance

Before examining Tier One and Tier Two separately, it is helpful to understand why the system is divided into tiers at all.

Texas separates school funding into tiers to define two distinct functions. Tier One represents the basic program that every district must provide. It includes the foundational educational services offered to all students. These funds come from a combination of local property taxes and state revenue.

Tier Two represents enrichment. These funds allow districts to raise additional revenue beyond the basic program, but only within state-controlled limits. Tier Two funding is supposed to offer local flexibility, but it is still governed by statewide formulas that restrict how much districts can raise and how much the state will supplement.

The purpose of this tiered structure is to require local communities to fund a base level of education while also providing a controlled avenue for enrichment beyond that base. Over time, political negotiations and court rulings expanded and complicated the tiers, creating the system Texas uses today.

How the Foundation School Program Works in Texas School Funding

The Foundation School Program determines how much funding each district is entitled to receive. A base amount per student is set by law and then adjusted by district characteristics, cost factors, and student needs. These adjustments are layered on top of one another, resulting in hundreds of variations across the state.

Once a district’s entitlement is calculated, the state determines how much must be paid for with local property taxes and how much must come from state revenue. If local taxes do not cover the entitlement, the state fills the gap. If local taxes exceed the entitlement, the excess becomes subject to recapture.

This structure places the state at the center of all funding decisions. Local tax collections matter, but only insofar as they satisfy or exceed the entitlement determined by statewide formulas.

Tier One Funding in Texas School Finance

Tier One funds the basic educational program every district must provide. Although often described as a cost-based entitlement, the base funding amount is not tied to updated cost-of-education studies. It is a policy number adjusted through factors that have accumulated over decades.

These adjustments include cost-of-living indexes, transportation allocations, sparsity factors, and small or midsize district adjustments. None of these adjustments reflects current educational costs with precision. Many are legacy provisions that persist due to political pressure or historical circumstance.

Tier One represents the majority of school funding, yet it remains opaque and difficult for taxpayers to understand. Districts focus heavily on navigating Tier One’s formula incentives rather than on demonstrating efficient use of the funds.

Tier Two Funding and Enrichment Taxes in Texas School Finance

Tier Two allows districts to raise enrichment funds above the Tier One level. The state provides differing levels of support for different enrichment tax rates, creating two categories of enrichment funding. Some enrichment tax effort receives a higher level of state support and are not subject to recapture. Other enrichment tax effort receives a lower level of support and are fully subject to recapture.

Because the Legislature sets the limits on enrichment taxes and determines how much the state will support, Tier Two funding is not purely local control. Districts that believe they are exercising local choice are often navigating limits imposed in the state budget.

Despite its limitations, Tier Two is the closest thing Texas has to flexible local funding.

Local Property Taxes and Their Role in Texas School Finance

Local property taxes fund most of Texas’s public education. Districts levy taxes on property values within their boundaries to generate operational revenue for schools and to repay debt for buildings.

Rising property values increase district revenue even without tax rate hikes, which places heavy burdens on homeowners and businesses. Because local revenue increases when property values rise, the state reduces its share of funding accordingly. This creates an inverse relationship in which taxpayers carry more of the cost as the state’s responsibility shrinks.

There is no constitutional requirement that school funding must come from property taxes. Texas could choose to replace the school maintenance and operations tax with state general revenue. With fiscal discipline, controlled spending, and responsible budgeting, the state could phase out the school M and O tax entirely. Reducing or eliminating this tax would provide meaningful, broad-based property tax relief, unlike targeted exemptions that shift the burden onto those who do not qualify.

This is the most effective path to long-term property tax relief.

Recapture and Robin Hood: Redistribution in Texas School Finance

Recapture requires property-wealthy districts to return excess local tax revenue to the state for redistribution. This process is designed to equalize funding across districts with dramatically different property values.

In practice, recapture functions as forced redistribution. Taxpayers in one community subsidize districts elsewhere, breaking the link between taxation and representation. Recapture discourages local fiscal responsibility because taxpayers cannot rely on their own revenue staying within the community.

Recapture grows as property values increase. It is one of the clearest examples of how the school finance system treats local revenue as a statewide resource.

Attendance and Student Counts in Texas School Finance

Texas funds schools based on the average number of students who attend each day, not simply how many are enrolled. If students are absent, districts lose funding, even when fixed costs remain the same.

The state then adjusts attendance through weighted counts for students in certain categories. These weights change the total student count for funding purposes but do not necessarily reflect modern cost realities. Weighted adjustments also create inequities between districts and encourage formula manipulation rather than instructional improvement.

Funding based on attendance and weighted multipliers makes the system harder to understand and more sensitive to fluctuations unrelated to student progress.

Student Weights and Allotments in Texas School Finance

Texas uses student weights to provide additional funding for particular educational needs. These weights are intended to address the costs of educating students with additional needs, but many weights are outdated and not tied to modern educational costs.

Because districts are not required to spend weighted money directly on the intended student populations, weighted funding often fails to translate into targeted services. Students with similar needs can generate different funding amounts depending on district circumstances.

A student-centered model would direct weighted dollars to the student rather than the district.

Tax Compression and the State’s Role in Local Property Taxes

Tax compression lowers local district property tax rates by replacing local revenue with state funds. This process is necessary to prevent district tax rates from functioning as a statewide property tax, which the Constitution prohibits. Compression reduces local tax burdens while ensuring that school districts remain fully funded.

Texas Policy Research supports tax compression as the superior method of delivering property tax relief. Compression reduces tax burdens for all taxpayers rather than providing selective benefits to certain groups. Unlike exemptions such as an increased homestead exemption, which simply shift burdens to renters, businesses, and those who do not qualify, tax compression reduces the overall tax rate and provides fair, equitable relief.

Compression is a genuine tax reduction. Exemptions are often political messaging tools that hide redistribution behind feel-good language while increasing the long-term burden on those outside the favored category.

Texas should pursue structural compression to the point of eliminating the school M&O tax entirely.

Bond Elections and Facilities Funding in Texas School Finance

School districts rely on local bond elections to finance buildings, renovations, and major capital projects. These bonds are repaid through the interest and sinking tax rate. Because property wealth varies significantly across regions, bond capacity and success rates vary widely.

Districts with strong tax bases can fund expansive facilities more easily. Districts with weaker tax bases struggle to pass bonds or generate sufficient revenue for needed improvements. Facilities funding is separate from operating funding and remains one of the most unequalized areas of Texas school finance.

These disparities place pressure on taxpayers and contribute to affordability issues statewide.

Charter Schools and Their Role in Texas School Finance

Charter schools are public schools, but their funding structure differs significantly from traditional school districts. Charters do not levy property taxes. They rely solely on state funding. This means they operate without access to local tax revenue, bond taxation, or appraisal-driven revenue growth.

This arrangement makes charter schools a form of school choice within the public system. Parents choose charters directly, and charters must remain financially and academically responsive to families in order to remain in operation. They are accountable both to their boards and to the parents whose enrollment decisions determine whether a charter survives. This dual accountability sets charters apart from traditional districts, which receive guaranteed funding regardless of family satisfaction.

The funding differences between charters and districts highlight broader inconsistencies in Texas school finance and underscore the need for student-centered reform.

How Education Savings Accounts Fit Into Texas School Finance

Education Savings Accounts represent a significant shift toward student-centered funding in Texas, but the new program is far from universal and carries structural limitations that shape how it interacts with the broader school finance system.

Texas’s ESA program, known as the Education Freedom Account, was created during the 89th Legislative Session and will begin operating in the 2026 to 2027 school year. The Comptroller’s final rules now outline how the system will function, who may participate, how funds may be spent, and what accountability requirements apply. Although the ESA program marks a long-awaited step toward educational freedom, it does not fundamentally reform the state’s school finance system and remains separate from the Foundation School Program.

ESA Eligibility and Who the Program Serves

A student may participate if they reside in Texas, are a U.S. citizen or legal resident, and are eligible to attend a public school or public prekindergarten program. However, a child may not be enrolled in a public school while using ESA funds, because participating students cannot be counted toward a district’s average daily attendance.

Prekindergarten eligibility follows existing state rules, meaning the program prioritizes students in categories such as income status, limited English proficiency, homelessness, foster care, or military family status.

Parents must provide documentation proving residency, lawful presence, income, and disability status. The Comptroller verifies documents electronically when possible to reduce administrative barriers.

Funding Caps and the Prioritized Lottery System

Although eligibility is broad, participation is not. Lawmakers capped the program at one billion dollars for its first biennium. Because demand is expected to exceed that limit, the Comptroller must use a prioritization system before conducting a lottery.

The order of admission prioritizes siblings of accepted participants, students with disabilities in lower-income households, families below certain income thresholds, and students from middle-income and higher-income families in descending order. Higher-income families are limited to a small share of total program funding. Applicants not chosen are placed on a waiting list.

This design ensures that the program does not operate as a statewide choice system. It is deliberately capped and structured to serve a small percentage of students.

Award Amounts and What Families Can Expect

Students attending private schools may receive around 85% of the statewide average of state and local funding per student. Students with disabilities can receive significantly more, reflecting the greater cost of specialized services. Homeschooling families may receive a limited amount for materials and services, but cannot apply ESA funds toward homeschool tuition or unapproved providers.

This reflects a narrower program design than ESA models in other states, where families have greater flexibility to allocate funds across full-time private schools, microschools, hybrid models, tutoring, or customized learning networks.

Approved Providers and Spending Rules

ESA funds may be used for a range of educational expenses, including tuition, curriculum, tutoring, textbooks, therapies, assessments, transportation, and certain forms of technology. All purchases must flow through a state-administered payment platform and must occur only with approved providers. Providers must meet licensure standards, undergo background checks, and be approved by the Comptroller.

These safeguards are designed to prevent misuse of funds. At the same time, they create participation barriers for microschools, learning pods, homeschool cooperatives, and emerging models that do not fit neatly into traditional accreditation or licensure frameworks. This makes the Texas ESA program more restrictive than universal models in other states.

Oversight and Enforcement

The Comptroller may suspend accounts, halt spending, require corrective action, or permanently remove families or providers from the program for violations. Evidence of fraud must be referred to prosecutors. These rules ensure accountability but also centralize program oversight in the Comptroller’s office.

How ESAs Interact with the Existing Funding System

Texas’s ESA program is funded entirely outside the Foundation School Program. The dollars do not come from local property taxes, do not reduce district entitlements, do not affect recapture calculations, and do not alter average daily attendance for public school finance. Districts retain their entire local tax base even when a student uses an ESA.

This structure means ESAs empower families without creating immediate fiscal impacts on district budgets. It also means ESAs do not structurally reform the existing finance system, which continues to depend heavily on local property taxes and redistribution formulas.

How Texas’s ESA Program Compares to Universal Models

Universal ESA programs in states like Arizona, West Virginia, and Florida allow all students to participate and allow dollars to follow students fully, not through a limited, capped structure. These programs often generate long-term fiscal savings because funding shifts from public systems to flexible, lower-cost private or hybrid learning models.

Texas’s program does not operate this way. It is capped, heavily administered, and dependent on the Legislature reauthorizing funds every biennium. Its narrow design limits competition and innovation and does not meaningfully challenge the monopoly structure of public education.

Why School Finance Reform Matters

Texas school finance influences property taxes, educational outcomes, district budgets, and state spending. The current system is built on centralized formulas, redistribution mechanisms, and local property tax dependence. This structure creates inefficiencies, reduces transparency, and undermines local control.

Texans have the opportunity to pursue structural reforms that prioritize students, protect taxpayers, and restore simplicity to the system. By slowing the growth of government spending, directing recurring state revenue to replace school property taxes, and continuing to expand student-centered options like ESAs, lawmakers can deliver meaningful, permanent property tax relief and create a funding model that aligns with Texas’ principles of liberty and limited government.

Understanding how the current system works is the first step toward reform. With clear priorities and disciplined budgeting, Texas can move toward a modern finance system that funds students rather than formulas and supports educational excellence across the state.

Texas Policy Research relies on the support of generous donors across Texas.

If you found this information helpful, please consider supporting our efforts! Thank you!